Geo Washington's letters

Introduction

Four centuries and eleven generations separate George Washington from the last of his English ancestors to reside in Washington Parish, County Durham. Although he dismissed his roots as simply “from the north,” surviving correspondence in the Library of Congress reveals a fleeting but significant exchange between Washington and Durham officials in 1770 and 1797.

Washington as Executor of Thomas Colville’s Will

By 1765, George Washington had resigned his commission in the Virginia Regiment and settled at Mount Vernon to pursue life as a planter with his wife, Martha.

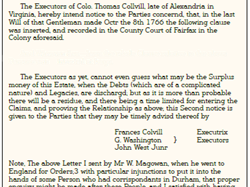

That same year he agreed to serve as an executor of the will of Colonel Thomas Colvill(e), a fellow retired officer, originally from Newcastle, Northumberland. Colville died in 1766, leaving behind tangled debts, uncompleted Virginia land sales, and four Co. Durham relatives of his wife named in his will as beneficiaries of any residue after other matters had been settled.(Colville has purchased much of his estates from the Earl of Tankerville, the Member of Parliament for Northumberland).

“And Whereas my Mother Catharine Colvill has several near Relations in Durham, of the names of Stott, Wills, Richardson and a Woman named Catharine Smith. It is my Will and desire that the Overplus or residue of my Estate when sold as aforesaid (if any overplus there be) be divided into four equal Parts; and that each of the beforementioned Stott, Wills, Richardson and Smith have one fourth part of the said overplus of my Estate; My meaning is, that those of these names the nearest related to my said mother or their direct descendants have each, their fourth Parts of the said residue after having made sufficient Proof of their respective relationship to my said Mother; and they enter their several Claims, and make the Proper proofs as aforesaid to my Executors within five years after my decease—”

Legal complications ballooned over the next three decades as Washington endeavoured to discharge debts and identify beneficiaries across two continents.

Correspondence with Durham Beneficiaries

Washington and his co-executors placed notices in American and English newspapers in March 1768 inviting anyone named Stott, Wills, Richardson, or Smith in Durham to come forward with claims which they would have to file in colonial Virginia courts.

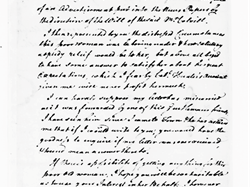

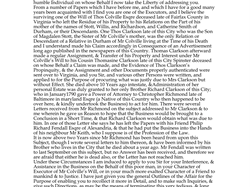

In May 1769, William Peareth of Usworth Place in the Parish of Washington, Co. Durham—newly enriched by coal mining—wrote on behalf of Dulcibella Stott, a likely cousin of Colville’s mother. Although his first letter is lost, a surviving follow-up from May 25, 1770, describes her as a “poor woman dependent on charity.”

Washington’s reply, dated September 20, 1770, expressed regret that ongoing debts and land disputes prevented him from disbursing any funds. He advised Durham claimants to seek relief through the Chancery Court or a public office in Newcastle.

(William Peareth -born 1734- was a significant owner of land and coal mines, whose father, also William -1704 to 1775- was the Clerk to the Alderman of Newcastle and had built Usworth Place in 1856).

The Unresolved Estate and Final Claims

The Revolutionary War further delayed settlement of Colville’s estate. By 1796, Washington—now President—was the sole surviving executor of the will’s residue, amounting to £932 17s 7¾d held in a Maryland bank, an amount George described as 'disappointing'.

He filed suit in a Virginia court early that July and again called on English claimants via the London Gazette between November 1796 and January 1797.

On May 12, 1797, George Pearson, Clerk of the Peace for Durham, wrote on behalf of Richard Clarkson, a surviving relative of Dulcibella who had died in 1773). Washington’s response on September 13 confirmed court deadlines and warned against spurious claims, directing all inquiries to the bank. But the will had been proved in March 1797, so it could be most English beneficiaries never received their legacies before Washington’s death on December 14, 1799.

Revival of Washington Old Hall

In the mid-20th century, local historian and headteacher Fred Hill spearheaded efforts to restore Washington Old Hall, the ancestral home of Washington’s forebears.

Between the 1930s and 1950s, Fred organized bicentennial commemorations, transatlantic flag exchanges between Biddick School and Washington, DC, and fundraising appeals to American donors. Without doubt he would have highlighted this correspondence between George Washington and William Peareth and George Pearson when lobbying the great and good in the USA and Britain

The restored hall was officially reopened by the US Ambassador in September 1955, solidifying the tangible link between the first President and the parish that gave the name to his family.

Conclusion

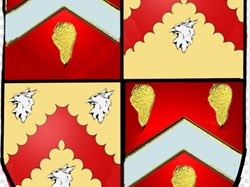

This singular body of correspondence stands as the only known direct link between George Washington and the parish that originated his illustrious name and coat of arms. Although the complexities of an 18th-century Anglo-American estate prevented any meaningful inheritance from reaching County Durham, the episode underscores the legal, geographic, and familial entanglements that still bound Great Britain and it’s ex-colonies.

Appendices 1 & 2 contain the full texts of the 1770 letters and the 1797 exchange, respectively.