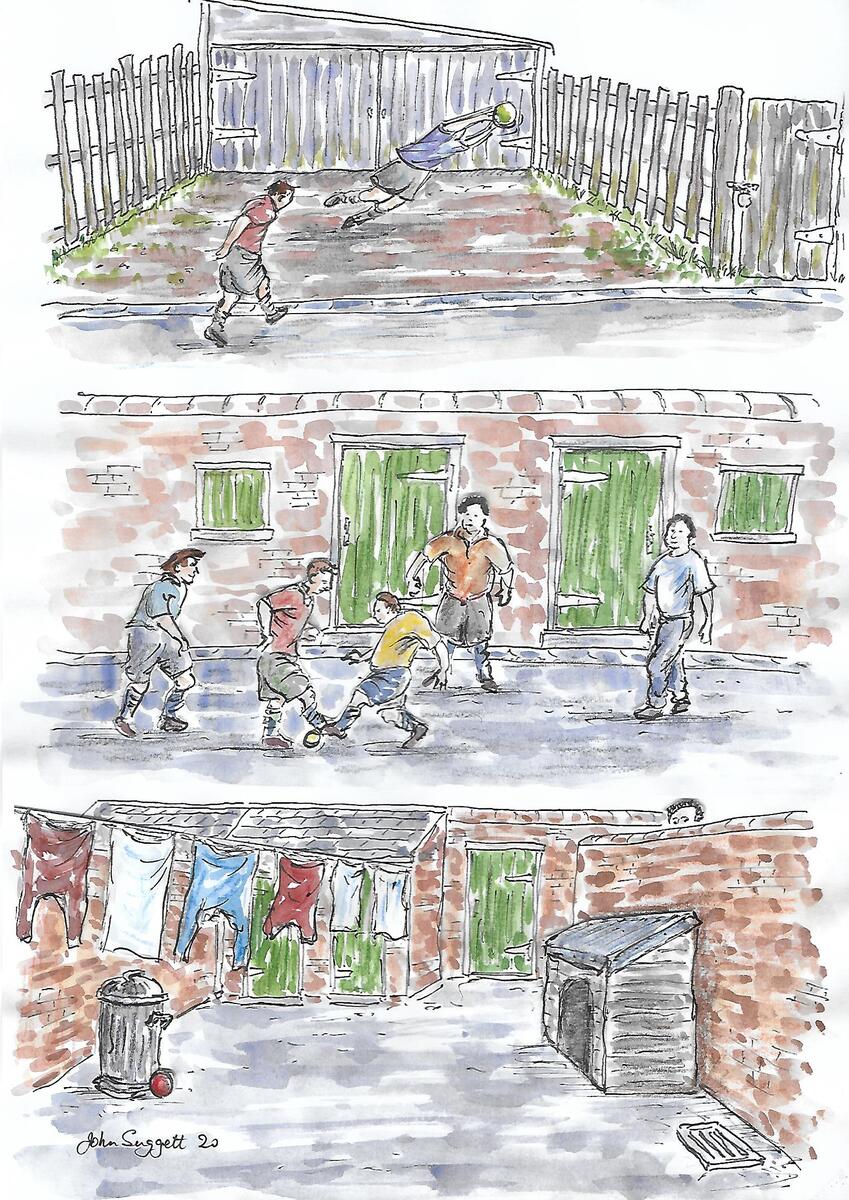

Back Street Football

The back lane and street ends were our football and cricket pitches and it was there that we developed our skills. Cricket was played mainly in the space between the ends of the terraced houses but football was our main back-street activity. The narrowness of the space between the brick walls and the high wooden garden fences opposite meant that tackling was frequent and robust, whilst dribbling, ‘screening’ and ball control became essential skills to develop. Tackling, tripping, ‘hacking’ (shin kicking), colliding and general rough play toughened us up and it should come as no surprise, therefore, that good footballers emerged from our back lanes. One of my brothers became a schoolboy international and made a career in the professional game whilst the other played to a high level in non-league football.

The football game which we usually played we called ‘doors’ (or, sometimes, ‘gates’). ‘Doors’ could be played by two or more players and usually involved the use of a tennis ball or something of a similar size. In one version of the game, each player ‘adopted’ a door which he would defend whilst trying to score a goal in someone else’s door. Another version, only used when there were a lot of participants, was where the players formed two teams which each defended its own door whilst attacking the other. This, of course, led to passing the ball - a luxury and skill not available when it was ‘every man for himself’.

Goals were scored by kicking, flicking, back-heeling or heading the ball so that it struck an opponent’s door. The door itself had to be struck and arguments developed if there were disputes as to whether or not the ball had struck the door frame which was deemed to be a goalpost or crossbar so disallowing any claim to a goal. This problem could be alleviated if the doors could be left open so that the ball would go into the back-yard and confirm that a goal had been scored. This arrangement was preferred as long as sufficient ‘friendly’ doors were available for all players. I say ‘friendly’ because some householders objected, quite vociferously at times, to their door being used as a goal. Some never allowed their doors to be used but, on those occasions when the inhabitants were known to be ‘out’, we might take the opportunity to make use of their doors. I’ll refer to these as ‘unfriendly’ doors.

On those occasions when the ball went over a wall into an ‘unfriendly’ back yard, someone had to be designated to retrieve it. The procedure was, usually, that the last person to have touched the ball had to retrieve it. This led to disputes at times but there was generally someone among us who would be brave or precocious enough to open a gate and rush in and out quickly. Some volunteered because they enjoyed the challenge and didn’t mind too much if they were shouted at.

Unfortunately, some back-yards contained sheds, piles of timber, dog kennels and other ‘stuff’ making finding the ball, let alone retrieving it, not always easy. If the ball had entered an ‘unfriendly’ yard, one solution was to gain access to a ‘friendly’ yard and climb the wall separating the yards – usually by means of a strategically placed dustbin - to try to determine the location of the ball. Once the ball had been ‘spotted’, a plan of quick retrieval could be plotted. If the ball could not be seen in these circumstances, guesses had to be made about its likely whereabouts. Under sheds was always a problem because you rarely knew what was under the shed and whether or not the ball was stuck. On such occasions, a stick of some sort was often needed on retrieval missions. Often the ball had rolled onto a drain cover which were usually located quite close to the window of the living room or scullery (kitchen) so that recovering the ball unseen was unlikely. Occasionally a ball could become wedged in gaps under coal-house doors. Even more difficult were those back-yards where balls could roll under lavatory doors.

We got to know back yards pretty well and games were rarely stopped altogether because a ball could not be found and retrieved. There were, however, a few gates which were usually bolted and ball-recovery from these had to be effected by climbing over walls or, occasionally, by climbing onto the slate roofs of the outside buildings (coal-houses and lavatories). Only the daring climbers, and I was not one of them, went on such missions to those yards. As I recall, my friends Keith and Bob, were among the leading exponents of such ventures.

I mentioned the variations in the ‘doors’ game and, of course, the more the participants, the longer the stretch of street that was needed for the individual door game. It was surprising how easy it usually was to resolve problems such as the close proximity of individual doors and on a willingness to ‘change’ doors because some were easier to defend than others - some had a concrete step which required a shot which lifted the ball off the ground. So we adjusted the game to suit the differing ages and skills of the players.

We faced similar problems in retrieving the ball when it went into the allotment gardens on the other side of the lane. Most of our fathers were coal-miners and many spent lots of their leisure time in their gardens growing vegetables and keeping hens and sometimes rabbits. Some men resented kids entering their gardens and possibly damaging plants which had been carefully nurtured. We learned to take care and to walk on garden paths until the ball could be located and retrieved with minimal damage. Similar approaches to ball-retrieval had to be adopted to ‘unfriendly’ gardens as we used for back yards. When plants were flourishing and in ‘full leaf’, retrieving a ball would prove impossible and days elapsed before it would mysteriously reappear.

Occasionally we would set up a game of football at the street end. Two teams were organised with jumpers for goalposts and a ball larger than a tennis ball was used. These games required goalkeepers whilst passing the ball became more important because the pitch was longer and wider. The street end, however, was mainly reserved for playing cricket. But that’s another story!